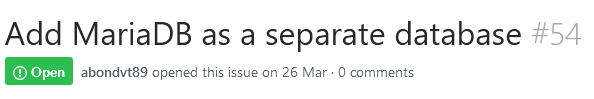

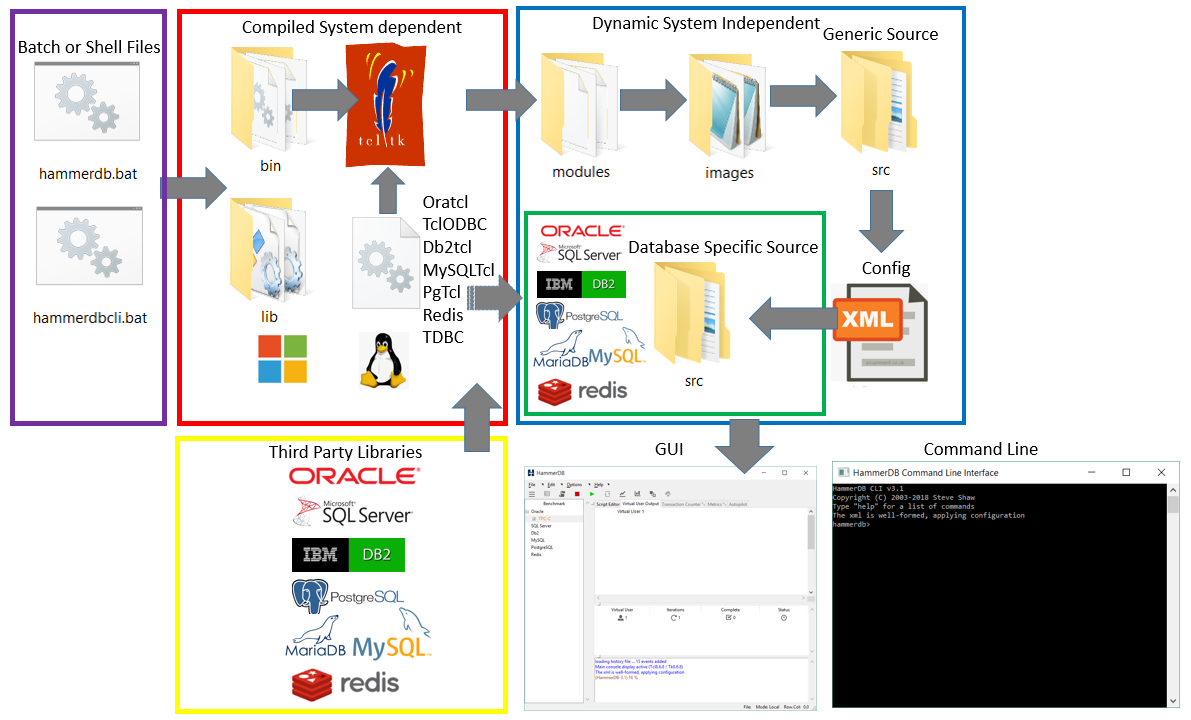

HammerDB is open source and all of the source code is available at the sourceforge Git development site here https://sourceforge.net/p/hammerdb/code/ci/master/tree/ or the github mirror here https://github.com/sm-shaw/HammerDB. This Git repository is updated with every release. In fact all of this source code is also included in readable form with each and every release. However if you have downloaded the source code and are looking to add features or make modifications such as adding new databases you may be wondering once you have the source code where to start. This guide to HammerDB concepts and architectures is aimed at helping you understand how HammerDB is built and how it can be extended and modified.

Programming Languages

When you download the source code for HammerDB you can see that the programming language it is written in is called TCL . TCL is a dynamic or interpreted language where the code is compiled into bytecode at runtime. It is important to understand at the outset that HammerDB is written in TCL because of the unique threading capabilities that TCL brings. This article Threads Done Right… With Tcl gives an excellent overview of these capabilities and it should be clear that to build a scalable benchmarking tool this thread performance and scalability is key. In contrast for example Python has the Global Interpreter Lock or GIL – “the global interpreter lock, or GIL, is a mutex that prevents multiple native threads from executing Python bytecodes at once. This lock is necessary mainly because CPython’s memory management is not thread-safe“. Therefore only TCL provides the foundation for building a tool such as HammerDB although Python can be loaded in the threads if desired. If you are not familiar with TCL you can also see that it is closely associated with a graphical user interface toolkit called TK. For HammerDB if you run the command-line version you are using TCL only, if you are running the graphical environment you are using TCL and TK. (Note that for the features used HammerDB will only run with TCL/TK 8.6 or above). So if you have downloaded the source code or the pre-packaged version and look for example in files under the src directory you will see a number of files with a .tcl extension that you can read – these are identical in both the source code and the pre-packaged version. It is of note that we have not discussed the operating system yet, that is because the source code and the code included with the pre-packaged versions is identical whether it is running on Linux or Windows on x86-64 architecture (or any other platform). That is a slight exaggeration as there are some architectural differences (such as command-line console interaction) however these can be managed with a statement such as follows:

if {[string match windows $::tcl_platform(platform)]} {

Otherwise the code is the same on all platforms. Clearly however there is a difference between platforms as you can tell from the download page and when you download the pre-packaged version you have and additional bin and lib directories that are (mostly) unique to a particular platform. These bin and lib directories are not included with the source code. TCL was designed as a language to be closely tied with C/C++ and at this lower level there is the compiled TCL (tclsh) or TCL/TK (wish) interpreter and supporting libraries. You can download and compile TCL/TK 8.6 or above yourself and replace the existing interpreter to be able to run the HammerDB interface from the source code by adding the bin and lib directories. However HammerDB will not be able to connect to a database yet and the librarycheck command included with the CLI gives an indication why.

HammerDB CLI v3.1

Copyright (C) 2003-2018 Steve Shaw

Type "help" for a list of commands

The xml is well-formed, applying configuration

hammerdb>librarycheck

Checking database library for Oracle

Success ... loaded library Oratcl for Oracle

Checking database library for MSSQLServer

Success ... loaded library tclodbc for MSSQLServer

Checking database library for Db2

Success ... loaded library db2tcl for Db2

Checking database library for MySQL

Success ... loaded library mysqltcl for MySQL

Checking database library for PostgreSQL

Success ... loaded library Pgtcl for PostgreSQL

Checking database library for Redis

Success ... loaded library redis for Redis

hammerdb>

Database Extensions

Also written in C HammerDB includes the pre-compiled extensions to the native interfaces for the databases that HammerDB supports as well as other supporting packages for functions such as graphing. Some of these packages have been modified from the original open source packages to ensure the correct functionality for HammerDB. All extensions have been compiled with gcc on Linux and MSVC on Windows for the x86-64 platform and require the presence of the compatible database library at runtime. For commercial databases this third-party library is the only non-open source component of the stack.

| Database |

Extension |

| Oracle/TimesTen |

Oratcl 4.6 |

| MS SQL Server/Linux and Windows |

Debian patch version of TclODBC 2.5.1 updated to 2.5.2 |

| IBM Db2 |

updated version of db2tclBelinksy to add bind variable support as version 2.0.0 |

| MariaDB/MySQL/Amazon Aurora |

MySQLTcl version 3.052 |

| PostgreSQL/Greenplum/Amazon Redshift |

PgTcl Pgtclng version 2.1.1 |

| Redis |

In-built pure TCL client |

| Trafodion SQL on Hadoop (Deprecated in HammerDB v3.0 ) |

TDBC included with TCL |

Other Extensions

| Functionality |

Extension |

| Clearlooks |

GUI Theme for Linux (but can be used on Windows) |

| Expect |

Console functionality for command-line functionality on Linux |

| tWAPI |

TCL Windows API used for command-line and CPU agent functionality on Windows |

| tkblt |

BLT graphical package extension for metrics for both Linux and Windows |

Pure Tcl Modules

In addition to compiled extensions there are also a number of TCL modules located in the modules directory, these extensions are similar to the packages in the lib directory however the main distinction is that almost all of these modules are written in TCL rather than compiled extensions written in C. These modules may also call additional packages for example as shown below the ReadLine module calls either Expect or tWAPI depending on the platform.

package provide TclReadLine 1.2

#TclReadLine2 modified to use Expect on Linux and Twapi on Windows

if {[string match windows $::tcl_platform(platform)]} {

package require twapi

package require twapi_input

...

}

} else {

package require Expect

Loading Extensions and Modules

The key command for loading extensions and modules is “package require”, for example the following extract at the top of the Oracle driver script shows the loading of the compiled Oratcl package as well as the common functions module for the TPC-C workload.

#!/usr/local/bin/tclsh8.6

set library Oratcl ;# Oracle OCI Library

#LOAD LIBRARIES AND MODULES

if [catch {package require $library} message] { error "Failed to load $library - $message" }

if [catch {::tcl::tm::path add modules} ] { error "Failed to find modules directory" }

if [catch {package require tpcccommon} ] { error "Failed to load tpcc common functions" } else { namespace import tpcccommon::* }

It should be clear that HammerDB is easy to extend by adding a new package into the lib (compiled) or modules (Pure TCL) directories and an example of how this is done is shown with adding Python support. The include directory contains the platform specific C header files for this purpose.

Agent

The agent directory contains the agent code to be run on the system under test to gather the CPU utilisation information. On Linux this runs the mpstat command on Windows mpstat is provided by HammerDB.

Images

The images directory contains TCL files with the images used by HammerDB encoded in base64 format.

Config

The configuration for HammerDB is defined by a number of XML files in the config directory. HammerDB is modular meaning that this configuration determines the files and directories to load from the src directory at runtime. At the top level is the database.xml that determines the other database configurations to load. Note that the commands field in this file only determines which words to highlight in the graphical text editor rather than defining the commands themselves.

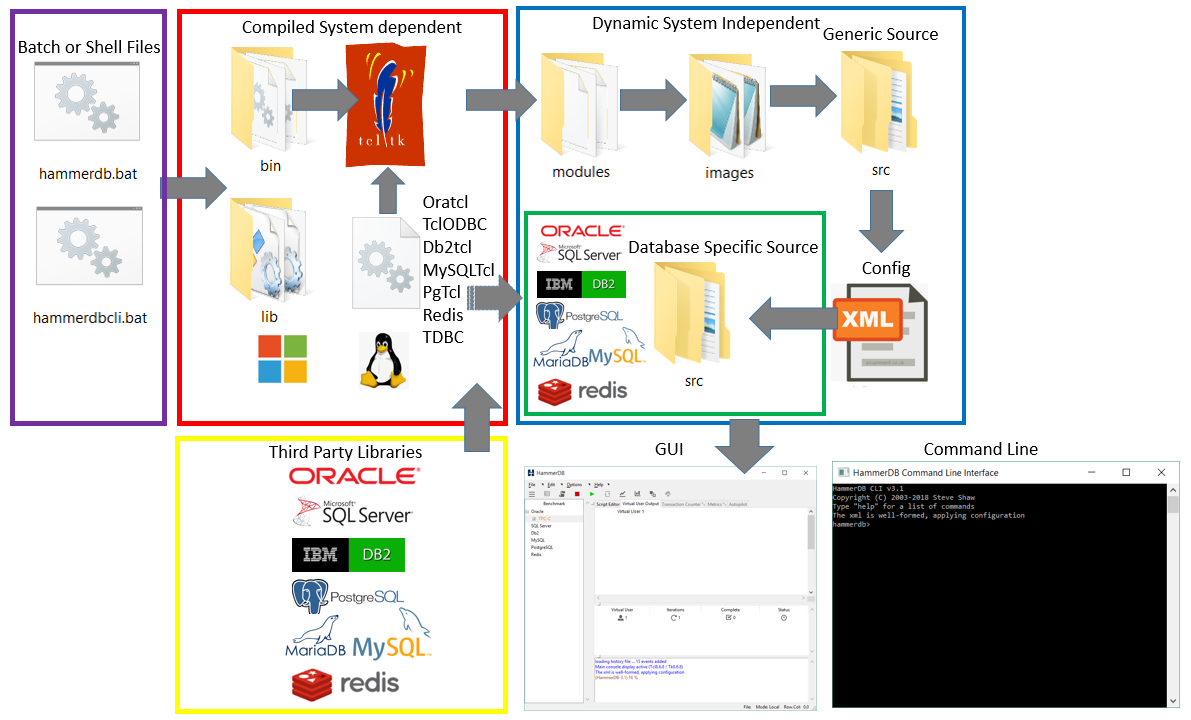

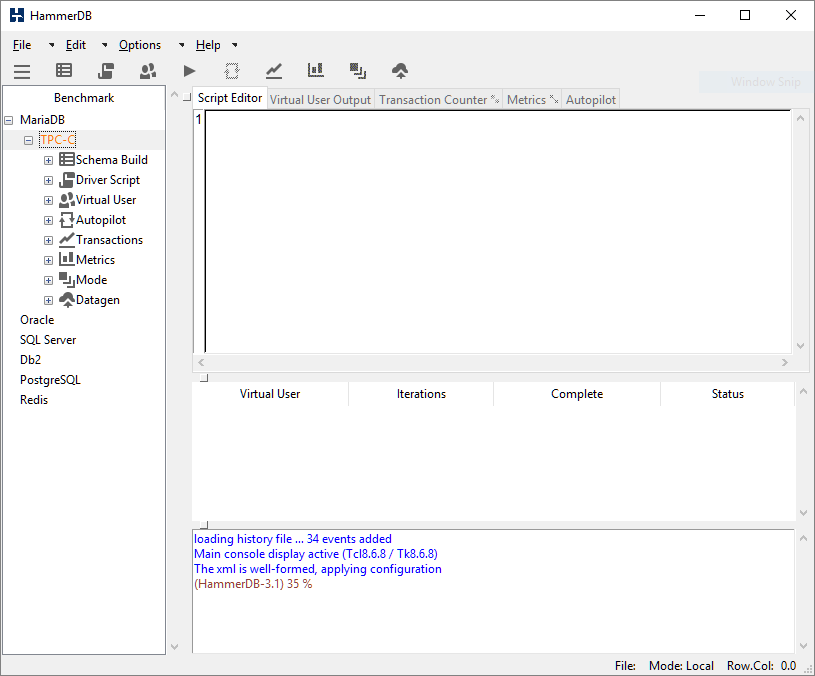

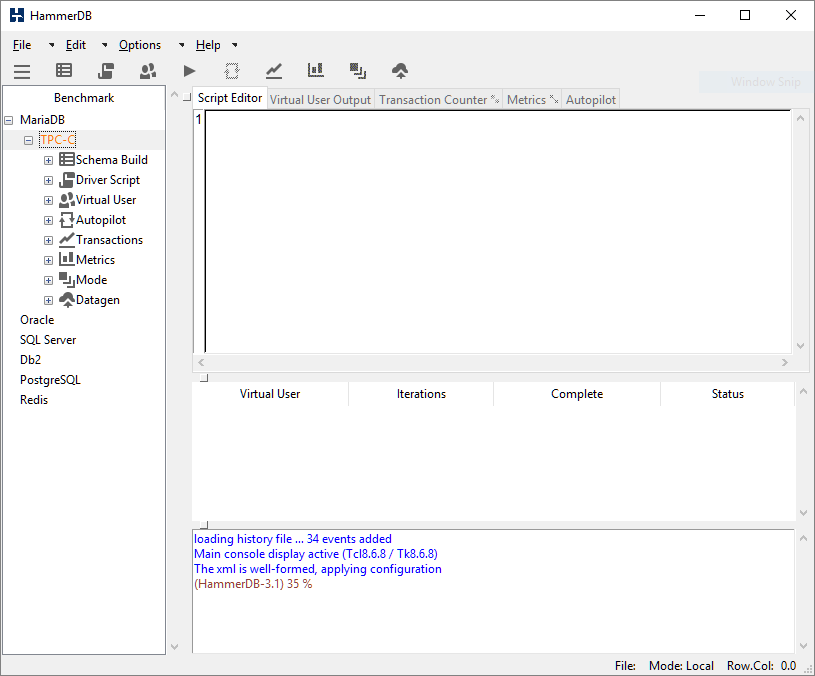

Starting HammerDB

When you start HammerDB GUI on Linux the hammerdb file is a bash script file that calls the Linux compiled wish (window shell) executable that then runs the TCL commands incorporated within that shell file. On Windows there is an external batch file that calls the Windows compiled wish and then runs TCL commands within the hammerdb file. For the command line it is the TCL shell that is run rather than wish. The hammerdb file acts as a loader that loads the modules, the icon images and the generic source, the XML based configuration is then loaded followed by the database specific components dependent on this configuration. The GUI or command line interface is then started. As virtual users are started the database specific packages and workload specific modules are loaded into the virtual user threads. The following diagram illustrates the process. Note that as the diagram illustrates most of the code is shared between both command-line and GUI implementations and what and how the virtual users run this code is identical, therefore both GUI and commmand-line produce identical results.

XML to Dict

As HammerDB is modular under the src directory is a generic directory for shared source and a directory for each of the databases that has the same name as the XML configuration file for that database in the config directory. HammerDB reads the XML at startup and manages the parameters internally in a 2 level nested dict structure per database. For example for MySQL the dict is shown and the retrieval of a single value.

HammerDB CLI v3.1

Copyright (C) 2003-2018 Steve Shaw

Type "help" for a list of commands

The xml is well-formed, applying configuration

hammerdb>puts $configmysql

connection {mysql_host 127.0.0.1 mysql_port 3306} tpcc {mysql_count_ware 1 mysql_num_vu 1 mysql_user root mysql_pass mysql mysql_dbase tpcc mysql_storage_engine innodb mysql_partition false mysql_total_iterations 1000000 mysql_raiseerror false mysql_keyandthink false mysql_driver test mysql_rampup 2 mysql_duration 5 mysql_allwarehouse false mysql_timeprofile false} tpch {mysql_scale_fact 1 mysql_tpch_user root mysql_tpch_pass mysql mysql_tpch_dbase tpch mysql_num_tpch_threads 1 mysql_tpch_storage_engine myisam mysql_total_querysets 1 mysql_raise_query_error false mysql_verbose false mysql_refresh_on false mysql_update_sets 1 mysql_trickle_refresh 1000 mysql_refresh_verbose false mysql_cloud_query false}

hammerdb>puts [ dict get $configmysql connection mysql_host ]

127.0.0.1

hammerdb>

As the options boxes in the GUI are filled out or values set at the command-line these values are stored and retrieved from these underlying dicts. At the top level the database.xml file determines the database specific data is read and the GUI populated at runtime rather than being fixed. For example changing the description field in the database.xml file as follows:

<name>MySQL</name>

<description>MariaDB</description>

<prefix>mysql</prefix>

<library>mysqltcl</library>

<workloads>TPC-C TPC-H</workloads>

<commands>mysql::sel mysqluse mysqlescape mysqlsel mysqlnext mysqlseek mysqlmap mysqlexec mysqlclose mysqlinfo mysqlresult mysqlcol mysqlstate mysqlinsertid mysqlquery mysqlendquery mysqlbaseinfo mysqlping mysqlchangeuser mysqlreceive</commands>

</mysql>

Will then display as follows in the interface.

Also note that the library field allows another library interface to be modified and recompiled or multiple version of libraries used for different databases.

Once the XML configuration is loaded the database specific files are loaded according to a directory in the database name and file names determined by prefix and the following purpose.

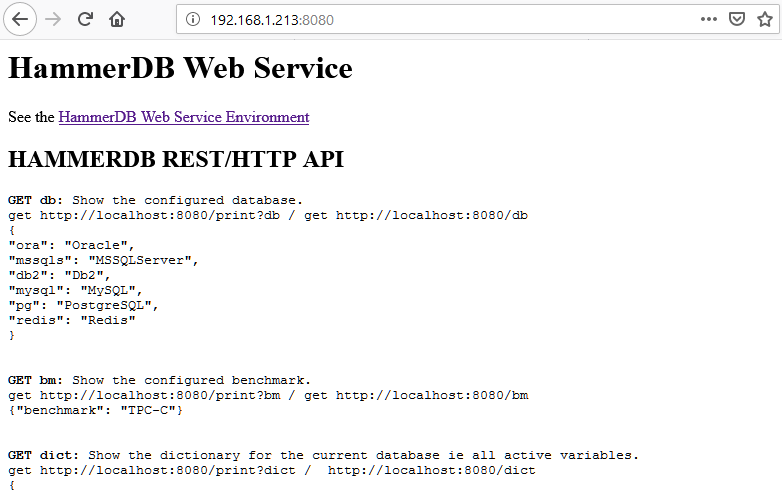

hammerdb>print db

Database Oracle set.

To change do: dbset db prefix, one of:

Oracle = ora MSSQLServer = mssqls Db2 = db2 MySQL = mysql PostgreSQL = pg Redis = redis

hammerdb>

| Extension |

Purpose |

| met |

Graphical metrics, currently only completed for Oracle |

| olap |

Analytic workloads, currently TPC-H related build and driver |

| oltp |

Transactional workloads, currently TPC-C related build and driver |

| opt |

Graphical options dialogs, takes values from database specific dict and allows modification and saving |

| otc |

Database specific online transaction counter |

Therefore for example in the directory /src/db2 the file db2opt defines the options dialogs when the db2 database is selected to load and store the dict based values. Then when a schema build is selected or driver script loaded the scripts are populated with those values entered into the dialog.

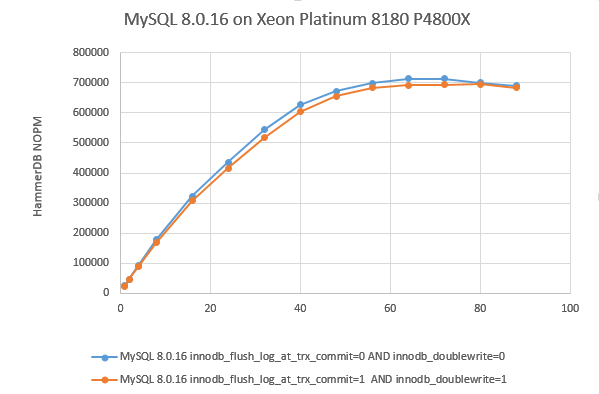

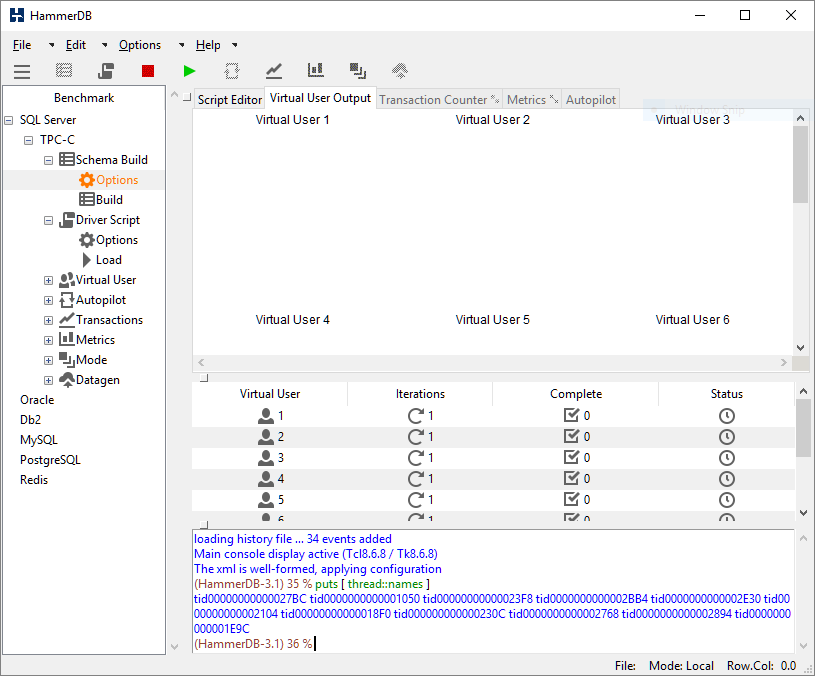

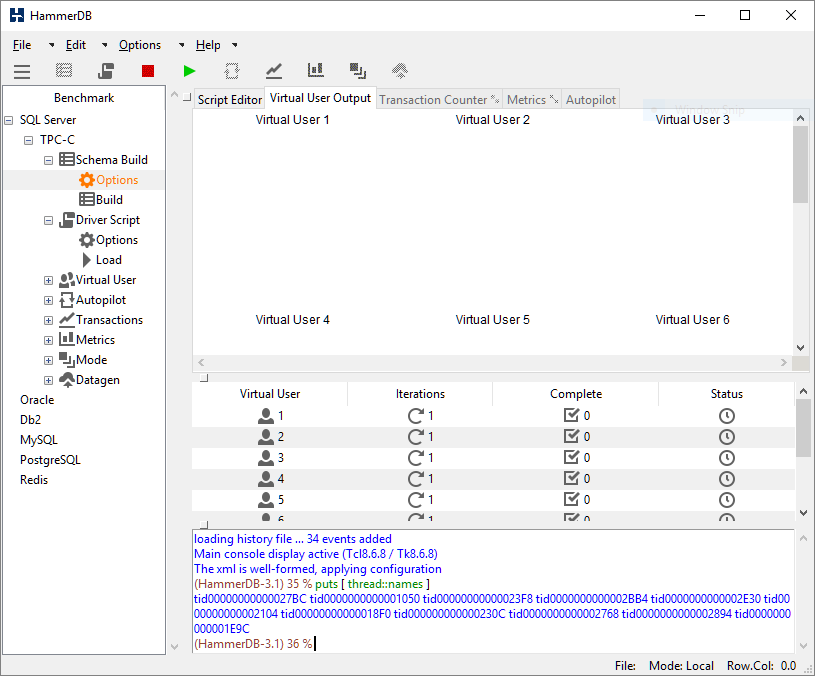

Virtual Users

Virtual Users within HammerDB are operating system threads. Each thread loads its own TCL interpreter and its own database interface packages. If you have not read the article Threads Done Right… With Tcl then now is a good time to do so to understand why HammerDB is so scalable. (Note that the metrics interface and transaction counter also run in threads).

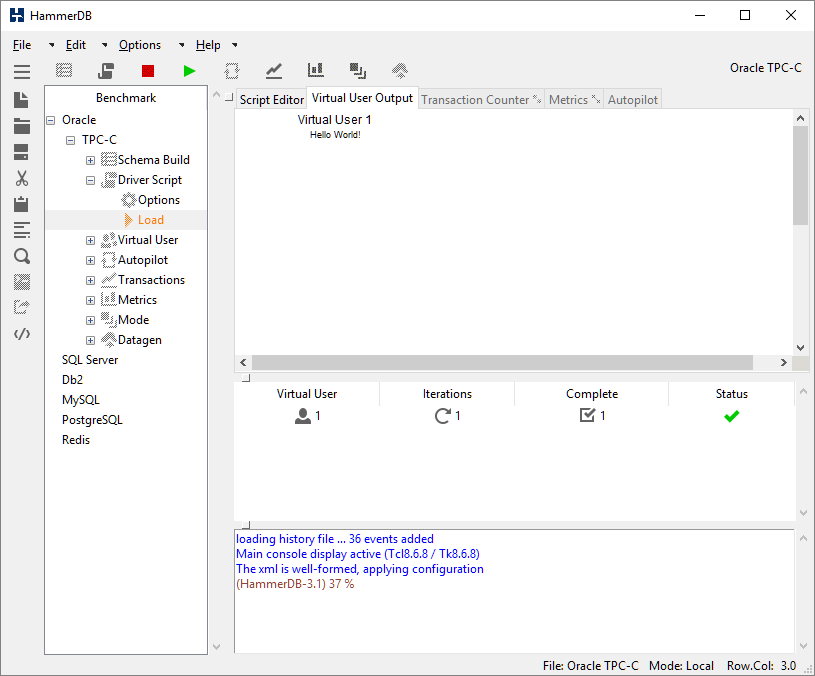

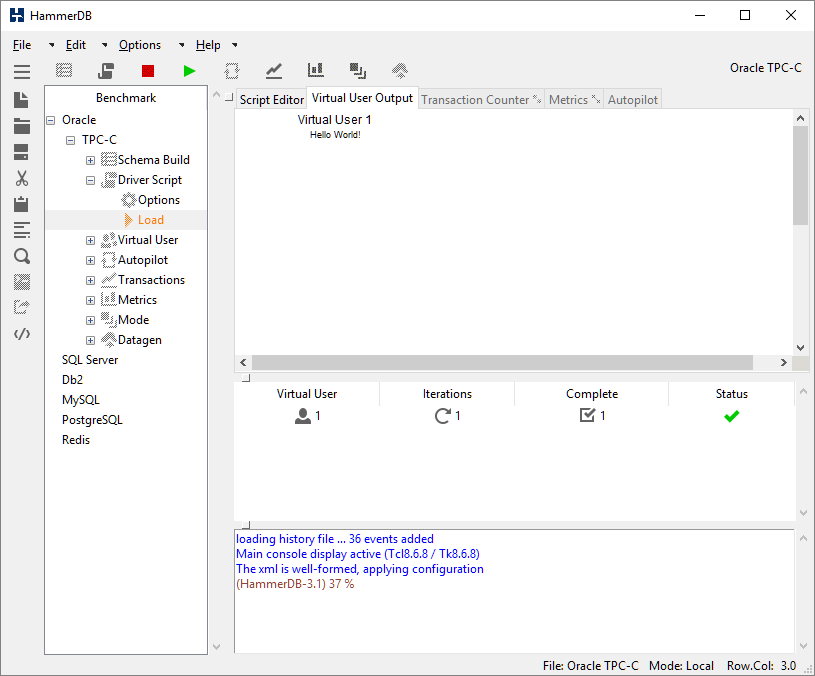

For example on Windows drilling down on the process explorer shows that the threads are evenly allocated to a different preferred CPU thereby making the best possible utilisation of the resources available. When the virtual users are run the threads are posted the script in the Script Editor in the GUI (or the loaded script for the command line). At its simplest the following is a Hello World! program in TCL.

#!/usr/local/bin/tclsh8.6

puts "Hello World!"

Load this into the script editor and run it (or for one virtual user use the “Test TCL Code” button and the Virtual User will receive and run the program.

Using the File -> Save dialog you can modify existing scripts and then save and reload them for later use.

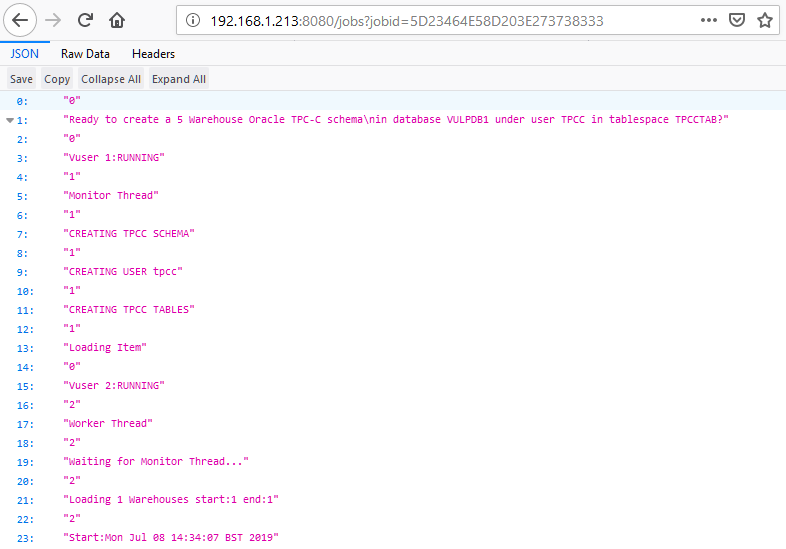

Running the Build and Driver Scripts

For the schema build or timed tests each virtual user receives and runs an identical copy of the script however is able to do something different. Each virtual user or operating system can identify its own thread id and therefore can be tasked with running a different part of the workload accordingly. This is how multiple virtual users will load a different part of the schema or how the virtual user that monitors a workload is identified. Also the threads can “talk to each other” and respond to user input such as pressing the stop button using thread shared variables. Otherwise overheads are minimal each virtual user will run entirely independently without interference from other threads and without locking overhead. Therefore running HammerDB on a multi-core and multi-threaded CPU is strongly recommended as you will be able to take advantage of that processing power. Output from virtual users are displayed to the virtual user output window. Note that operating system displays are not thread safe and cannot be updated by more than one thread at a time, therefore each virtual user sends its output to the master thread for display. Clearly a “Test Script” will not be able to generate the same level of throughput as a “Timed Script” for this reason. HammerDB also manages the virtual user status and reports any errors produced by the virtual users to the console.

Autopilot and Modes

In addition to direct interaction HammerDB also provides an autopilot feature to automate testing. This feature to be used in conjunction with timed tests allows for multiple tests to be run consecutively unattended without manual interaction. The way this feature works is for a timer to run at the user specified interval and at this timer interval HammerDB will automatically press the buttons that manual interaction would do. From a conceptual standpoint it is important to understand this as autopilot actually presses the same buttons that a user would, the only difference is that this is on a timed basis. Therefore if you want an autopilot run to complete successfully ensure that the time interval is long enough for your test to complete. There is no autopilot feature in the command-line tool as it is easier to script this functionality with the command-line.

Typically HammerDB will run in Local Mode however this modes feature allows an instance of HammerDB to be created as a Master and then multiple Slave instances connected to HammerDB to be controlled by the Master through network communication. This feature has been designed for scenarios where the user wants to direct a workload specifically at multiple database instances in a cluster or in a virtualized environment.

Summary

It should now be clear that HammerDB is a simple and modular application yet extremely powerful and high performance because of the multi-threaded architecture and design. HammerDB is also highly extensible and extensions written in C can be added to support for example new databases (or existing extensions used). After this simply adding a new config file and adding these details to database.xml and creating a new directory under the src directory is all that is needed to add another database to HammerDB. Similarly new workloads can be added by modifying existing files. HammerDB will then take care of running these workloads either graphically or at the command line.

Of the most importance however it should be clear that HammerDB is completely and entirely open source. TCL itself is open source, all of the database extensions are open source and the database libraries themselves with the exception of commerical databases are open-source as well. Also clearly all of the HammerDB code is open-source and readable within each installation so if you desire you can inspect literally every line of code right from the TCL interpreter to the extensions and HammerDB if you wish to do so. Therefore nothing is hidden and nothing is proprietary giving absolute confidence in the results that HammerDB produces. You are also empowered to modify, add and contribute improvements. HammerDB really is all about making database performance open-source and demystifying the often hidden aspects of database benchmarking from workloads to results.